How did Latvia become a place for your research and work?

I was an undergraduate student at the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire and I went to a study abroad fair my first semester of university. I studied political science and I always knew I wanted to study abroad. There were basically two programs where I could study Political Science in English. I had taken Spanish in high school, the language was interesting, but I wasn’t that interested in it. My choices were Costa Rica, Spain or Latvia. And I’m from Minnesota, I love cold weather, so I was like, “I’m not going to Costa Rica or Spain, I’m choosing the coldest place I can go to.” So initially I chose Latvia because of the weather. The most hilarious thing about this is that this was in 1999. I’m American, right, I have family from Poland and Czech Republic from a long time ago, so I’m half East-European. But I told my mom, “Mom, I’m going to go study in Latvia” and she was like, “Is that in the Balkans?” And I’m like, “No, no, it’s the Baltics!” Because it was the 90s, the Balkans were in the news in the US a lot. It’s funny, because when I initially told my family I was going to study here they thought it was the completely opposite end of Europe. But now most of my family have actually visited Latvia. My husband and I have lived here, too, so basically now if you have met me, you know where Latvia is located.

In my university we had this study abroad program because of two Latvian American professors - Paulis Lazda and Irēne Lazda. Paulis Lazda was one of the people that helped start the Occupation Museum here. His family came over to the U.S. in the late 40s, as a displaced person, so he always wanted to start a study abroad program. When Latvia became independent, he did it. I think it was one of the first exchange programs to Latvia. I know that when I studied at the University of Latvia, I was one of only 20 exchange students, which is kind of amazing now, because there are a lot more at this time. It was a great time to visit Latvia. I was taught Latvian by former Peace Corps, because we were here 1-2 years after the Peace Corps left, so we had really great language instruction. At that time no one really spoke English, so you would go to class and learn how to order food in a restaurant and then you had to go and use it, which was the best way to learn a language. But yes, I chose to study here, because I like cold weather. Which doesn’t feel like that currently since the weather last week was really hot (laughs). I came here 20 years ago, and I have been coming ever since. And now I’m bringing my own students, since I’m a professor. I brought students for the first time last year and hopefully I’ll bring them again next year.

How would you compare your experience back then and your - and your students’ - experience now?

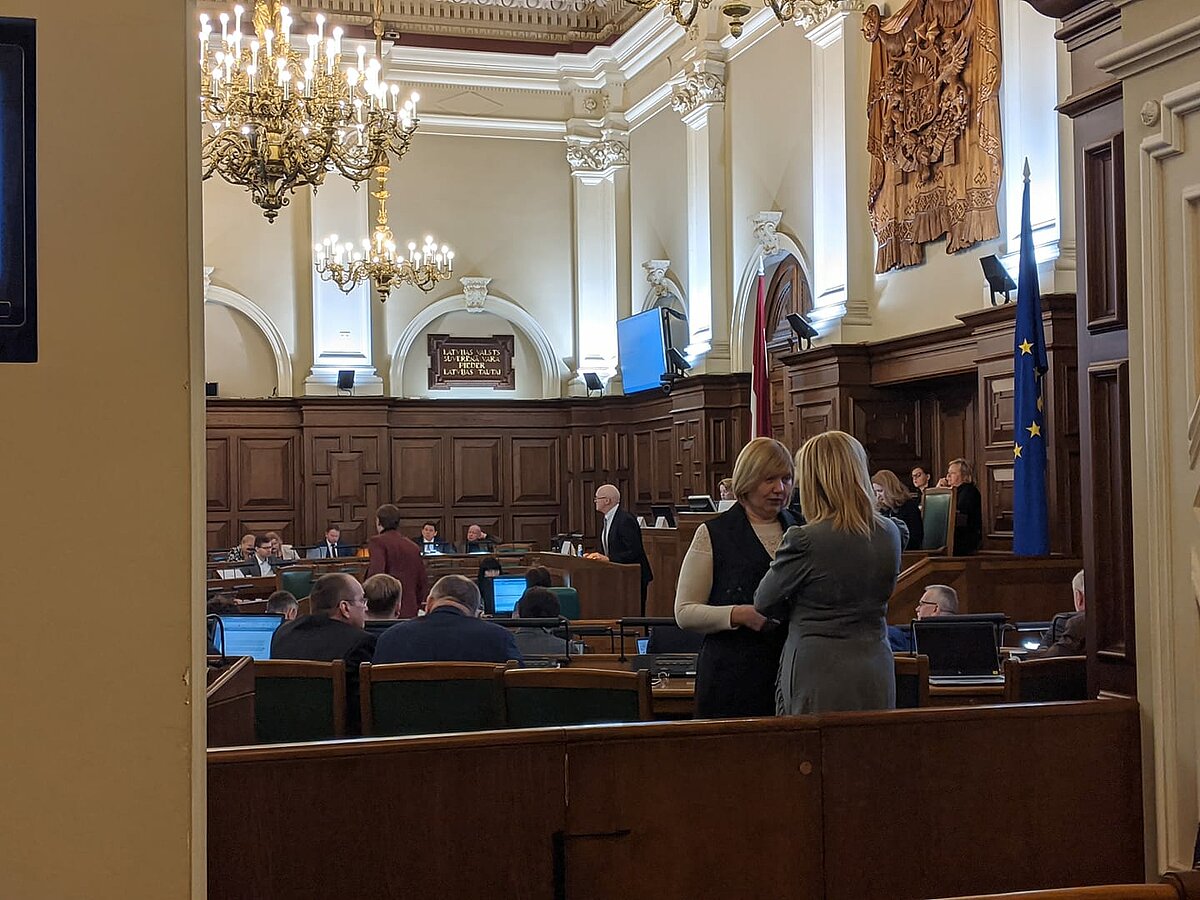

It’s interesting, because I think in the 90s things were a lot less clear. We didn’t know if Latvia was going to join the European Union, it hadn’t joined NATO. As a political scientist, things are much more open. When I took my students here, we went to the Parliament, we went and met with a former U.S. ambassador at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. I basically e-mailed the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and we were able to get a talk from the former U.S. ambassador. That’s pretty amazing to be able to have that experience. And then we went to Parliament. I study women and politics, and it was funny - we went on a Thursday to one of the open debates and I asked my students, “What’s the first thing you notice being here?” And they looked at the presidium and they’re like, “It’s all women!” Except for one, one man was the Secretary. It’s interesting to hear their impressions. It's also kind of difficult. I love Latvia, I come here almost every Summer. I have a host family that I lived with, so to me it’s like a second home. And then, bringing my students here, we were on a flight on the way over and I was like, “What if they don’t like it?!” Because I love this place. Thankfully, they did, too, so it was OK.

They liked the food and I think for them having people speaking English all the time made it really easy to communicate. It made it very easy to travel with them. I get annoyed with that sometimes, with people who always want to speak English to me because I speak Latvian and I do have an accent, but when I’m in the stores or getting coffee, a super basic thing and they automatically switch to English and I’m like, “No!”. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve talked to baristas and told them, “No, I studied Latvian for, like, 5 years! I can order a coffee!”

I think that Europeanization and the openness of the society makes it a lot easier to study, bring students and travel to Latvua. Especially when compared to the U.S., because we can take mass transportation. We took local buses. We went to Bauska and took the bus to Rundāles pils. The locals were super nice. I think that when most Americans study abroad, they hire a coach service and stuff to take them around and I was like, “Nope! We’re doing it the way locals do it!” We took all local buses and travelled around. I think they left with a good impression of it. A bunch of them got Namejs rings, which I thought was kind of cool. We taught them about the legend and everything. And now I go back to America and I’m teaching in class and I see someone wearing a Namejs ring and I was like, “Oh, yeah, you studied with me!”

You taught a course on gender and politics. How was it working with students here?

It was interesting. I originally approached the chair of my faculty, Dr. Iveta Reinholde, and I said, “I would like to come to Latvia, I want to apply for this U.S. government scholarship.” She was very supportive, so I was thinking, “Ok, I’ll get like ten students.” Gender and politics, since it has never been taught here, is not usually a theme covered in many of the courses, and I ended up with 45 students! I think it shows that there is a need for a gendered approach to studying politics. I had Erasmus students, I had Latvian students. Most were political science majors. It was great to have that diverse variety ofstudents. We attended the March 8, International Women’s Day march. It was nice to see them start their activism and discuss how, “We need to march, we need to talk about the Istanbul Convention, we need to talk about women’s rights in the society.” Even though Latvia is 55% women and the level of women’s representation is relatively high in Europe, I think that it is something that needs to be studied and clearly there are students who are interested in it. Part of Feminist research is going out and doing research with the population that we study. So part of my research here is looking at women’s representation, so I had every student who could speak Latvian pick a member of the 13th Saeima to interview.. I think we were up to 26 of the 31 [female members of Saeima], which is pretty good! That’s one thing about conducting research in Latvia - people are really open and accessible, especially Members of Parliaments. When I told the students we would be interviewing MPs, they said “They’re never going to answer us!” There were MPs that took a little bit more work and calling, but most of the people were very open to talking to us, which, I think, surprised a lot of students, getting access to politics. I think it was a good experience for them, good experience for me.

The interviews were, of course, anonymous, and one of the last questions was about violence and politics. Research shows that about 40% of women in politics experience some level of violence or harassment. Thankfully no one has died here in Latvia, but there have been female politicians around the world who have been murdered when running for office. I think it was the most surprising thing for my students, to hear people who are members of government talk about how they’ve received threats on-line, via Twitter, Facebook, things like that. Almost all the students would come out of the interview and be like, “Wow, I’m really surprised that it happens in our country!” I think it was eye-opening for them, they got to learn a bit of an aspect of politics that they might never study. Also it was really great because some of the students took the class because they thought maybe it would be easy and then we would go and interview the MPs and then they would say, “This is really important research! We’re glad you’re researching women and politics in this country.” Even the students who were most apathetic about interviewing people usually left the interview like, “Wow, I guess this is important!” Which is good! You teach in class, but part of feminist research is actually going out and doing the research. It’s so much more rewarding.

And you do a lot of research in the Parliament too - can you tell more about your own fieldwork?

The research that I did with my students was actually part of it. We did about 17 interviews with students and then I did the rest with a research assistant. We continued where the course left off, but then every single Thursday until the coronavirus situation I was in Parliament, doing participant-observation research and looking at different gender dynamics that happen in the Latvian Parliament. I often wonder - in people’s treatment of the speaker - if they would treat a male speaker like that. Right now, I’m analysing the interruptions. Women in parliamentary debates, when they are speaking, are interrupted more often than men, so I’m really going through and counting all the interruptions. That’s the paper I’m working on right now, and I wrote a previous paper that should be published soon about if women are more likely to be crossed out on the list. You know, when you vote in Latvia you can cross people’s names out, and women are crossed out more often than men. Which is interesting, because I’m pretty sure no one has counted all of them. I went to the Central Election commission to ask about voter turnout data and the gentleman was like, “Wait, you counted every single plus and minus?” “Yup, I want to know.” Latvia has an interesting voting system. The fact that you can cross people out. Many electoral systems are closed where you can’t change the rank of people on the list, so that makes Latvia a very interesting case - to see if we do see women are not given pluses as often as men moving them into seat mandates. . In the 13th Saeima women were not given pluses as often, but the difference between men and women was less apparent in the pluses and minuses, and that’s part of the reason why we see such a significant increase of women.

The theme of gender and politics can be quite controversial, what attitudes towards your research how you encountered?

I was told by some people that I would not get any students in my class, that they wouldn’t be interested, so I definitely got pushback on that, but I would say that most of the MPs are really interested in what we’re doing. We asked questions such as “How did you get recruited into politics?” Theories show that women are recruited into politics because they have a family member in politics, or champion the outsider status, so it has been interesting to ask women how they started in politics. Many women started on the local level, we see a lot of women who serve in Parliament working in municipal councils, Rīgas Dome is a big starting out point for many MPs..

I was kind of nervous to interview the opposition parties, but I don’t think people interview them and they were really open to this. We had really interesting interviews with members of the opposition parties. They said, “I’m so glad that you contacted me!” And I was like, “Really?”. We had interviews that were over an hour long with people talking about their experience. I think when people do research on politics in Latvia they focus on the party leaders, the party structure, they don’t focus on individual MPs as much. And they definitely don’t focus on female MPs.

I wouldn’t say I have gotten a ton of pushback, but I’ve definitely gotten people who have said: “Oh, that’s… interesting”. Sometimes when I’m sitting in Parliament, I would get people looking at me, like: “Who is this foreigner?”. It would basically be me and journalists who would sit there every Thursday and when we started doing more interviews they realized: “That’s the lady that’s doing the research on the women. ”But honestly, I haven’t gotten any pushback on the research, most people have been very open to it. My colleagues at the University of Latvia, Social Science faculty have been very open to gender research. Communications and sociology are well known for gender studies, we just need to get political science there. Now there are graduate students who are interested in that, I hope we will continue this course online. We’re going to try to offer it every other year and see if we get the same interest. I’m hoping that the course can continue after I leave.

I was surprised that it didn’t exist already, in the faculty of Humanities we have the centre “Feministica Lettica” and gender is a topic explored in many different fields.

Yes, with Ausma Cimdiņa and Irina Novikova. All the feminist researchers in Latvia know each other! That’s one thing - we need to get gender studies into sciences, we need to get them into medicine, so there can be these new approaches. We are finding that with the coronavirus that it affects women differently than men, so we need these types of gender dynamics and feminist research in every faculty in the university, I think, and in every discipline because there are differences between men women that should be taken into account. In many of the interviews people told me that they’re not feminist, we had many interviewees who were very against the Istanbul Convention, which I thought was kind of interesting and surprising, too, because it is just a domestic violence legislation, but it comes down to this issue of gender and the word “gender”. Yes, and the terminology is tricky.

The terminology exists, but I think that my interpretation of the word “gender” is just “gender”. And many people think that with the Istanbul Convention it represents LGBT individuals. The Latvian Parliament is more conservative, so we definitely see the pushback, but everyone was really nice to talk to, even if they were “against feminism”. And that’s the thing about doing political science research - if I only interview the feminists, that would skew my research. We wanted to get a wide range of the MPs and learn about the research as a whole. If I only interviewed the [self-identified] feminists in the Latvian Parliament, it would be a handful of people. It was interesting to learn the wide spectrum of ideas, of policies. How women cooperate with each other in Parliament. We learned a lot about women taking coffee together, eating lunch together – and it is people who you see having acrimonious relationships in the Saeima will then turn around and go have lunch together, which I think is great. It shows that politics is politics, but then the personal relationships are kind of different. And the research says that we can see that kind of cooperation with female MPs around the world.

Your other research is concerned with human trafficking. Can you tell a bit more about your most recent work, “Diffusing Human Trafficking Policy in Eurasia”?

I studied in the University of Latvia in 1999 and then I came back as a Master’s student in 2007/2008. I took political science classes, but I also volunteered at centre “Marta”. At the time they were the only rehabilitation centre for victims of human trafficking in Latvia. Part of my research was to look at human trafficking issues in Latvia, so I volunteered there and got first-hand experience of the trafficking movement. I got to see where government policies were successful and where they failed. After my year here in Latvia I started my PhD, so I always knew I wanted to do something human trafficking related andthe seeds for the book were planted when I was working at the centre “Marta”. Then I started learning Russian and Ukrainian and I was able to expand my research and look at cases from Ukraine and Russia. The book basically looks at international policies on trafficking and how they diffuse to the national level. I focus on how they are adopted and transfer from the international level, with the Palermo Protocol, to Council of Europe conventions to the national level. and then how they are implemented.

Latvia doesn’t have as encompassing legislation as Ukraine or Moldova or Georgia, but they implement them relatively effectively, and I think that’s largely because Latvia is a small country. The Latvian government, I believe, cares about the people. In the 3 cases I looked at, the Latvian government was the only government to pay for rehabilitation services. In Ukraine they were paid for by international organizations. In Russia it was international organizations and now with the law on Foreign Agents most organizations are closed and can’t work with trafficking [victims] anymore, because it’s such a controversial issue. I’ve found that in Latvia the policies work relatively well and I think it’s because the government cares about the people. Latvia needs every one of you! (laughs). And in small countries we can see that policy implementation works.

Latvia also has a really great working group on trafficking. They’ve recognized different aspects of trafficking that have happened to victims in this country and have been able to respond to them. Latvia was the first country in the EU to have a law outlawing fiktīvas laulības, fictitious marriages, because they kept seeing Latvian women being exploited by third country nationals in Ireland and in the UK and they were able to respond very effectively. Fictitious marriages happen to many women in Eastern Europe and Latvia was able to respond more quickly than Slovakia, Lithuania and other countries.

It is interesting that you say human trafficking is a controversial issue, because it seems like such a clearly bad thing.

It’s controversial in Russia. The U.S. government has a Trafficking in Persons Report where they basically grade countries around the world for what they do according to the American perspective on human trafficking. But basically the U.S. government grades every single country, and grades are controversial. The U.S. gave Russia the equivalent of an F, which they were upset about and there has been significant backlash in that country based on trafficking.

For the report governments around the world give the U.S. statistics on trafficking arrests and the number of victims rehabilitated. The Russian government refused to give the U.S. government any of those numbers, because they thought, “If we don’t give them those numbers, they won’t give us a bad grade.” America still gave them a bad grade, and the U.S. emphasis on human trafficking is a big reason why it is so controversial in Russia.

Getting back to a slightly lighter theme, relatively speaking. COVID-19 and this semester - how has this experience been for you?

What happened in the middle of March was that the U.S. government cancelled my Fulbright fellowship here, they told me to go home. And I said no. I decided to stay in Latvia. I have been coming here for 20 years and I basically live a block from my Latvian host parents So I have family and friends here. I thought that it would not be a good idea for me to leave and go back home with the lines at airports.

It was interesting and frustrating for a number of reasons. The U.S. government cancelled my program. Thankfully my chair, Dr. Iveta Reinholde, was great, she helped me with visas and stuff, so I am really grateful to the University of Latvia and my connections here, because without them I would not have been able to stay here and finish my teaching and research. With the transfer of courses online I think the students were great and responding to that and it worked out well. For me the most frustrating thing was not knowing what was happening, because the U.S. government can force us to leave. Many Fulbrighters were forced to leave around the world and Fulbright is the most prestigious program sponsored by the U.S. government.. It is frustrating that they recalled, I believe, over 3000 people. I stayed. I wanted to continue my classes and my research. Again, a lot of it is based on the fact that I have been coming here so long. I was in Parliament on the Thursday and the Friday when they were debating the emergency situation. I heard the speeches from the health minister, and I felt confident that Latvia would be able to handle it. And it turns out I was right!

In retrospect I’m really glad I stayed; I was able to continue my research with the e-Saeima online. Covid kind of put a wrench in things, but I am thankful to the University of Latvia for working with me and making it so I could stay and continue to teach and finish this semester.

What has been your experience with learning Latvian?

At first we used to learn it and we would go out on the streets and practice it. Latvian is a difficult language, clearly. One thing about learning Latvian, everyone is super excited when they see foreigners try to speak Latvian. I was in a cab yesterday and the guy was like, “Are you Latvian? Are you American Latvian?” And when I said no, he was like, “How is that possible? How did you learn this?” People are always really surprised. I meet lots of foreigners who speak Latvian so I don’t know why people are still surprised. Latvian is difficult, but I think Latvians are more forgiving with grammatical mistakes.

I definitely think learning a language is an important aspect in not only conducting the research that I do and being able to spy on my students and know what they are talking about in class, but also in connecting with the culture and the people. I don’t think I would be able to have the relationships here that I did if I did not speak Latvian. I can’t tell you how many doors have been opened in my life because I speak this language. I’ve been doing interviews with MPs. I would e-mail them in Latvian and then they ask, “What language will we be conducting this interview?” And I said well “I wrote you in Latvian, so we’re conducting it in Latvian!” They are always surprised.

I should say too, I studied here and then I went and got a Master’s in Baltic Studies from the University of Washington, and that’s the only university in America that teaches Latvian. And that lectureship for the Latvian language professor was actually paid for half by the Latvian Ministry of Education Ministry. Again, I wouldn’t speak Latvian without the support from the Latvian government. I moved from Minnesota halfway across America to Seattle, and the only reason I chose that university was because they were the only one to teach the Latvian language. So that’s why sometimes when the young people in cafes speak English to me I’m like: “I moved thousands of miles to learn this language!”

Speaking of language and culture, as I understand you studied kokle?

Yes! Here’s my kokle [shows a musical instrument case]. I’m going to my lesson after this. One of my friends that I took Latvian lessons with here, she’s German and she started taking kokle lessons and I thought sabbaticals aren’t all about research and I thought I needed to do something cultural.

I will say, everyone told me, “Oh, it’s really easy!” but was harder than I thought. Latvians, you all either sing or you dance, in America they are much more stringent. I didn’t have any musical background, but I can now play two full songs, which is exciting after not that many lessons. And when I go back to the U.S. I actually had a Latvian American “meistars” make me a kokle. I rented this one [shows], because you can rent kokles in Latvia. So I’m going back to the U.S. to have my very own kokle and I can continue playing. I got up this morning and I was working on the song that I’m trying to play, so you get that feeling of accomplishment that you don’t always get from academic work, because academic work takes months. Learning and doing cultural things gives you a sense of accomplishment, and I will say, people are impressed when they hear I’ve been taking kokle lessons, too. So that’s another way to impress Latvians.

What have been some of your favourite places in Latvia?

Cēsis is my favorite city outside of Riga. Rundāles pils is amazing, too. Americans love castles - because we don’t have them. And for me it’s cool to see how things have changed. I visited there in the early 2000s and to see the transformation now, how much they’ve restored. And even Sigulda castle, the restauration there is impressive. That’s one thing that’s great about coming to a country continually for 20 years you get to witness all of the changes firsthand.

I went to Daugavpils, to the Rothko museum and I thought that was amazing. I was impressed that the Rothko family was able to donate and lend original works of art. For Jāņi we went to Kolka and I’d never been there. I always wanted to see it and that amazing. I had heard about the Līvi and the Livonian culture, and that was interesting to learn about, too. We went to a museum there and got some food from a random campground. The round, orange, carrot…

Sklandrausis?

Yeah, that! I never had that before. And that’s one thing I love about coming here. I still have things left to see. Eventually I have to do a road trip around Latgale. I’ve never been to Rēzekne, that’s on my list. There’s still lots more to see.

It’s so good that you have a positive outlook on the things you’ve seen here!

It’s funny, because I’ve never met a foreigner who really didn’t like it here. My Erasmus students all said, “Latvia is great!”. For me it’s surprising why other students choose to study here. It’s interesting to hear, but from my Erasmus students in class and all the foreigners that I’ve met that have lived here everyone has been very positive. I mean, people come here and they never leave! (laughs).

So we can hope that you will return to Latvia?

Yes! I will bring different students again next summer, we’ll see what happens with the Covid situation.

What are your other plans for the future - in your research and otherwise?

I’m hoping to write a book based on my research. I have to find a publisher, but I think the fact that I was able to get personal interviews with female MPs was really innovative, so I’m hoping to take the research that I did here and publish it in the U.S. I’m hoping to work on my kokle playing (laughs). I also want to bring more American students here. Since, I had a professor who brought me here when I was 19, it’s really great to be able to kind of pay it forward and bring my own students here. Now, my students write their senior theses on Latvia. For me it’s wonderful to have that experience as a student and now to bring my own students. To be a professor and pass that love for this country and Latvian culture onto the next generation of students is really something for which I am thankful

Akadēmiskais centrs

Akadēmiskais centrs