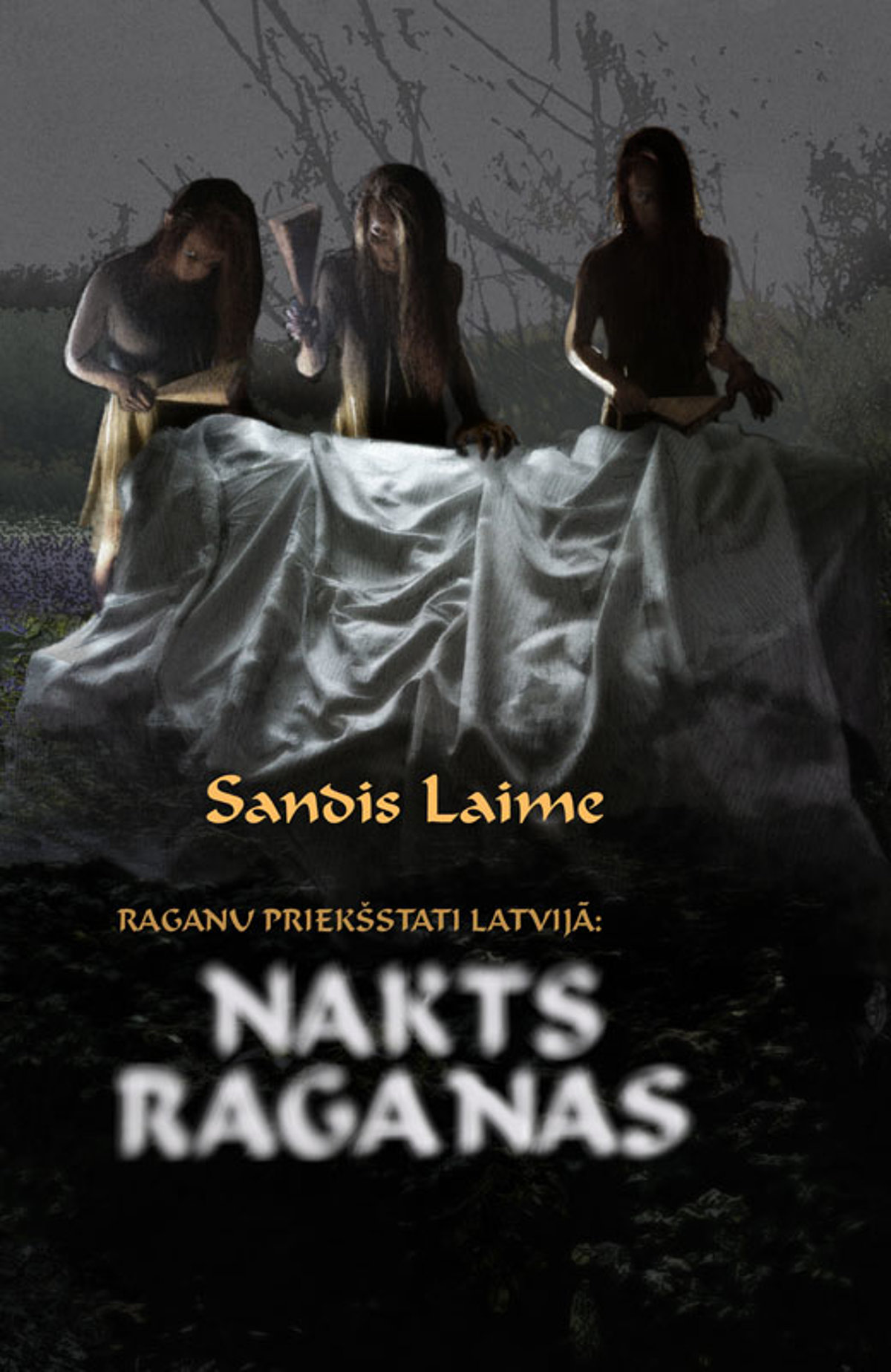

The researcher examined Latvian folklore to find evidence of virtually unknown night witches. Contrary to ‘traditional’ witches, these night witches do not ride a broomstick with a cat under their arm. Sandis Laime has studied the methods people once used to protect themselves from witches, and found out that even today some people still believe in night witches.

Laime got interested in witches by accident, as initially he intended to write his doctoral dissertation on sacred places (also called cult places). While Laime was gathering information on cult places, he came upon tales about witches’ places. The researcher discovered that some tales feature unknown witches, ‘They are called witches in tales, but their description differed from my understanding of witches. At that point, I asked myself the question: what a typical witch is.’ Laime realized it was a new and unexplored area of Latvian mythology. As Laime had a great desire to research the topic, he directed his studies towards the unusual witches.

Beautiful nocturnal laundress

Laime researched witches active at nights. Night witches are not real women, but spirits living in graveyards, lakes, cracks of rocks and elsewhere. These witches launder at night, an action symbolizing purification. Laime explains–the souls that cannot pass into the Afterworld after their death are purified on Earth. In tales, this process is pictured as laundering.

‘When these stories were recorded, the storytellers themselves could not explain what these witches are; they just depicted them as demons,’ says Laime. The researcher draws parallels between the beliefs about night witches in Latvia and other European countries. In some countries, people believe that night witches are the spirits of women who did not receive what they deserved during their lifetime. These could be women who died during childbirth, or stayed unmarried, or committed a great sin, for example, killed their own child. These women turned into demons and stayed on Earth after their death, becoming the so-called ‘unfortunate souls’.

‘In some regions of Latvia, people traditionally believe that night witches sit on tree branches, brush their hair and allure people. In Latgale, these witches try to tickle people to death. In Vidzeme, the people who disturb their laundering are forced to wander around until dawn,’ says Laime, explaining the popular beliefs.

Common names for witches are Bārbala, Trīne, Katrīna, Kade, and Kača. A typical witch is a young girl with loose golden hair, bare feet, and red, yellow, black, or white clothes. Sometimes witches can be completely nude. Laime stresses that loose hair belonging to the Afterworld. The researcher explains that loose hair was uncommon in traditional rural societies—married women wore headdress, while maidens had plaits. Witches are attractive, but there are ugly witches as well. In Latvia though, there are not as many bright descriptions of ugly witches as in neighbouring countries. Curiously, in other countries people believe that these witches have such large breasts that they need to put them over their shoulders to be able to do laundering.

New attitude: witches can be good

Laime jokes that now the word witch is used almost as a compliment. Most people also believe in ‘good’ and ‘bad’ witches. However, this word did not carry any positive connotations one hundred or just fifty years ago. Laime explains that distinguishing between good and bad witches emerged because people misunderstood the original meaning of the word. People think that in the past witches were women who could see the future and tell fortunes. Laime points out that there is no evidence of witches possessing such powers in Latvian folklore. Recently, German linguist Bernd Gliwa came up with a new explanation for the origin of the word, proving that initially the Latvian ‘raganas’ (witches) meant spirits, rather than fortune tellers.

The old Latvian beliefs have merged with the Christian attitude, since in medieval times Christians considered women healers to be witches. In the traditional Latvian society, however, women with healing powers were never called witches. Laime points out that dictionaries contain at least ten words to denote healers of that time, for example, pūšļotājs (sorcerer), zavētājs (enchanter), vārdotājs (charmer). The names depended on the methods practised by the healers.

Laime explains that the word ragana was first recorded in a witch protocol of the 16th century, but supposedly coined much earlier. The researcher points out that there are simply no older written sources. The word ragana was included in the first Latvian dictionary, published in 1638.

Laime has spent several years studying beliefs about witches. He jokes that witches have not visited him in his dreams, although he would not mind. The researcher admits watching movies and TV series about witches after learning how popular they are. Charmed, Buffy the Vamire Slayer, The Witches of Eastwick, among many others, have strongly influenced modern beliefs about witches. In the 21st century, these beliefs are shaped by the television. The archaic beliefs about night witches were changing in medieval times as well. For example, in the early modern period, some of the characteristics and activities of the demonic night witches were ascribed to the women with supernatural powers. Until the early 20th century, ancient beliefs about night witches remained intact only in the peripheral areas of Latvia.

Night witches still live in Viļaka, Latgale

The north-eastern Latvia is the focus of Laime’s research, since most of the materials on demonic witches were found in northern Vidzeme and northern Latgale. The researcher has found very few materials on night witches in other parts of Latvia. Laime reveals that names of territories in Latvia where the beliefs about night witches were widespread contain the word ragana (witch). People believed that witches live in witches’ hills, rocks, and marshes. Later, this word was used to name places where witches were executed. However, Laime points out that it is the case of very few places, mostly hills, as witches could hardly be burned in marshes. He adds that people are usually unaware of the origins of place names that serve as ordinary landmarks now.

It is important to know that night witches do not approach people in their houses. Instead, they attack people who enter their territory with most assaults taking place close to cemeteries. Calling a wolf is an archaic method to protect oneself from these witches. Laime explains that people believed wolves could tear the deceased in pieces if they tried to leave their territory. People are not allowed to do whatever they want in cemeteries; likewise, the deceased have their own code of conduct. To call a wolf, a person has to say special words, howl like a wolf, or simply tell witches, ‘The wolf eats witches!’ It is enough to mention a wolf to scare off a witch.

Another way to get rid of witches is to take off one’s belt. Laime explains, ‘Apparently, it is because the pants go down once the belt is off. People used to believe that all supernatural creatures are afraid of nudity.’ Lord’s Prayer is another method introduced by Christianity, yet there are no preventive means to protect a house from night witches. However, there are some methods to repel other types of witches, such as sorcerers or milk stealers. Since beliefs about these witches may have originated from the ancient night witches, Laime assumes the same methods can be used for all kinds of witches. Thus, people can put thistles around their house or leave a scythe on a threshold of a cattle-shed for witches to cut themselves.

The beliefs about night witches were widespread all around north-eastern Latvia in early 20th century. Now the popularity of these beliefs has decreased greatly, says Laime. The researcher was able to find some people in Viļaka who believe in demonic night witches. In this Latgalian town, there is also the Witch Hill (Raganu kalns). Laime says that Viļaka is a peripheral town, and in these territories archaic beliefs usually survive longer.

‘While I was doing my research, people told me the stories about night witches, the mysterious night demons, and how they have seen them appearing over a pond. These people still believe in night witches. If they believe in them, witches are alive, at least in northern Latgale,’ says Laime.

*In 2011, Sandis Laime defended his doctoral dissertation in philology, entitled Witchcraft Traditions in North-Eastern Latvia. Later, he used it as a basis for his monograph Beliefs about Witches in Latvia: Night Witches. Sandis Laime works at the Archives of Latvian Folklore, UL Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art.

About the publication series ‘Research’

The University of Latvia (UL) is the largest higher education establishment in Latvia bringing together Latvia’s greatest minds in natural sciences, social sciences and the humanities. The UL scientists’ discoveries and achievements bring Alma Mater closer to its aim of becoming a leading university of science recognised at both European and global levels. Since 2012, scientific achievements of UL researchers have been publicised in ‘Resesarch’ series. Every month you can learn about one of the researches on the UL website!

The scientific potential of the UL contributes to the Latvian national economy and sustainable social development!

Translated by students of the professional study programme Translator of the University of Latvia.

Translated by students of the professional study programme Translator of the University of Latvia.

LU konference

LU konference