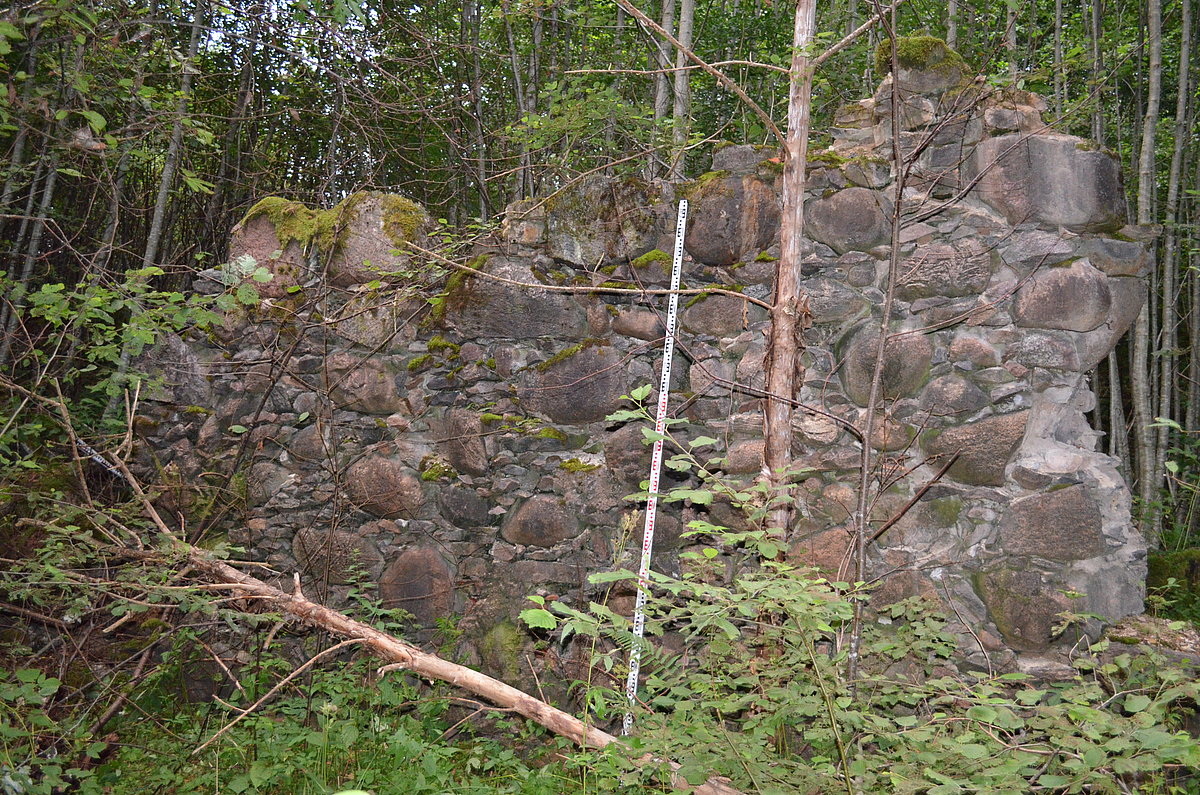

One of the project’s focuses is on iron manufactures of the Duchy of Courland and Semigalia times, which were located, for example, in Renda, Ezermuiža, Engure, Baldone, Lutriņi and Turlava, but, paradoxically, none of them had ever been archaeologically investigated. Historian Mārīte Jakovļeva has widely researched historical data about manufactures.

In Latvia, investigation of this type of objects is a novelty; however, it is quite a usual thing for the colleagues from Norway. One of the project’s experts, former dean of the LU FHP Andris Sne, also admits that Norwegian colleagues are more experienced in this type of investigation. “Historically, Norway has a very long experience in working with bog ores. Those deposits are also in Latvia, and iron was obtained on their basis on the spot, but, it should be noted that the mining efforts were also supplemented by imported iron.” Norwegian colleagues are also more experienced in investigating the technologies for processing of materials. “They are ahead of us in this particular area, but there are two aspects why we had chosen them, first, it is related to Norwegian financial instrument, where the rquirement is that partners have to be Norwegians, and, second, we focus on skills and their transfer, where they could provide useful advice,” A. Sne continues.

Swedish Vidzeme will be explored for the first time

The project will cover two longer periods – the Stone Age, where the focus is on flint processing technology, and the Iron Age, which includes the processing of iron. The most significant period to be focused on is the early modern period – the time after the fall of Livonia and the beginning of the Duchy of Courland and Semigalia. A. Sne explains this choice with the fact that there is much known about the Duchy; however, there is less information about the second part of Latvia – the 17th century Swedish Vidzeme. “Owing to M. Jakovleva’s research, we have the basis to start from; therefore, we will try to also look at Vidzeme for the first time, where there was both a different political power and different forms of economic activity.”

Since history is a big guessing game, it is impossible to determine precisely how and where certain processing technologies originated, and where the materials were imported from. “The Norwegian colleagues will help with the exact analyses of minerals, which are also planned within the project. The analysis of iron objects and their elements, as well as the determination of the chemical composition, could identify how much of the material is imported, with what methods it is obtained and combined, resulting in some weapon or a tool. Of course, it does not answer the question of the origin of people who have created those objects, though it will provide an insight into their knowledge, and then it will be possible to draw parallels and understand where the corresponding skills come from,” A. Sne explains the idea.

The objects that are made in the territory of present-day Latvia are similar to those in Norway: “If we look at the Stone Age, we classify it by stone processing industries, which cover large areas, and present-day national borders are irrelevant. These stone processing traditions cover the entire Baltic Sea region and stretch away to the North Sea area. We expect the same with the Iron Age, when endless motion of people, things and ideas took place. Of course, there should be also differences, but to obtain the best results from bog ores, there should be a single way of doing it, the obtained objects will be different, but the method will be singular,” says A. Sne.

The obtaining and processing of materials as a social process will be emphasised

The principal investigator of the project is UL ILH archaeologist Valdis Bērziņš. Within the project, he will pay most attention to the Stone Age. “Of course, the society and technology of the Stone Age are completely different things, though the major theme remains – how technologies are transferred in time and space. Attention will also be paid to the ways people have continued these traditions, that is, developed them or introduced their own innovations,” V. Bērziņš says. Speaking about peculiarities of the region, both specialists draw parallels between the Stone and the Iron Age, that is, there are no high-quality flint and iron extraction places, which means that the material is hard to process and requires greater knowledge. “The nearest high-value flint mining places are located on the territories of the present-day South Lithuania, Belarus and Poland. Seemingly, at that time, it was brought to Latvian territory by means of exchange or wandering. It has made the material very valuable; therefore, our tools have been smaller than, for example, in Denmark,” V. Bērziņš explains.

It proves the fact that the material was used sparingly. “Neither then, nor now is it possible to find flint in the woods as blueberries in the summer,” Andris Sne tells humorously. Direct similarities between the processing of stone and iron will not be searched for within the project, because the materials are quite different as to the method of processing and chemical composition. “Special tools and people to carry out the processing were required for both materials, it can even be said that a particular craftsman delivered this material to the public in a certain format,” A. Sne explains. Thus, the focus will be on the obtaining and processing of materials as a social process, where technologies have been transferred, developed and experimented with. “In various ages there has been a completely different society and environment, which, of course, changed, also the technologies themselves have undergone changes, but we hope that they could provide us with the opportunity to look at a certain historical period, and things that happened between the obtained mineral and society,” A. Sne continues.

As has been mentioned previously, former iron manufactures on the territory of Latvia will be explored within the project’s framework, and one of them will be investigated archaeologically. To the question of why manufactures are so underexplored nowadays, although many people are interested in them, A. Sne answers: “So far the attention has not been paid, because such topics are not popular, and in archaeological research tradition the greatest emphasis is laid on the cemeteries and domiciles, as well as modern big cities. Besides, it should be taken into account that we do not have many archaeologists, and we lack specialists on many issues. Therefore, we physically cannot cover all the topics.” It is yet unspecified, which of the manufactures will have the privilege to be archaeologically explored, because it will be determined by several factors, such as future research prospects as well as availability. According to the project plan, the existing information will be collected this year and archaeological site exploration trips to identify these places are scheduled for next spring. In one of the places (most scientifically promising, and easily available) small-scale archaeological investigations will be carried out. The materials obtained during these investigations will undergo chemical and physical analyses, in which we look forward to support from our Norwegian colleagues,” A. Sne explains.

Citizens are also invited to share their knowledge

This project will not do without public participation. Society can engage in it differently, for example, by keeping up with the development of the project on the Internet, as well as by participating in various activities over the next year. One of the challenges for participants of the project is the reconstruction of a 10th century iron smelting furnace, which will be based on data about the furnace in the historical Asote settlement. “All attempts to restore the furnace have been unsuccessful so far; though Norwegian colleagues have succeeded in similar experiments, therefore we hope for the best results, but nobody knows what will come of it,” A. Sne remarks. The reconstruction of the furnace will be available to the public as well and will take place in Ventspils. Those who are interested will have the opportunity to observe the excavations, which will take place at the site of one of the manufactures.

Before the project started, news arrived that could influence both its progress and results came. “We received information about a previously unknown archaeological site on the left bank of Daugava River, not far from the border of Selonia. A forester found some coal burning sites,” Valdis Bērziņš says, “and this also relates to our project, because charcoal is needed in large quantities to produce iron, and these coal burning sites are not explored in Latvia; although there have been many of them. By reporting things we have not known before, people invest in the project.” He also indicates that society considers archaeology a burden rather than an opportunity: “In other countries there is bigger interest from enthusiasts who provide important information about archaeological objects in their neighbourhood to archaeologists. People know their neighbourhoods better than anyone, but do not consider important to notify anyone about anything.”

Research – an opportunity for students

Since one of the parties involved in the project is UL FHP, students will also be given an opportunity to participate in excavations. “The project, of course, plans archaeological excavations, which are a part of archaeological outdoor work course. We think that approximately 10 students will be involved,” A. Sne says. “To study archaeology is one thing, but to experience it, we need to go outside. In recent years good traditions have developed, particularly, field work takes place in several areas simultaneously, rather than in one.”

When asked about the planned results, both Andris Sne and Valdis Bērziņš are very cautious, because it is hard to speak about particular results when the project has only just started and two years of intensive work are still ahead. “Our plans are ambitious, but the issues on which we expect results are: 1) flint processing – to find out where the raw material came from and how its processing traditions fit into Latvian archaeological material; 2) iron mining – to gather currently known information about the Iron Age and the Middle Ages, determining the basis for the prosperity of the new period iron processing; 3) to obtain more detailed statistics – manufacture sites during the Duchy, their maintenance condition, the amount of potential information; 4) to carry out archaeological excavations and physical and chemical analyses, which provide an insight into iron product composition and circulation; 5) to gather knowledge about the situation in the new period Vidzeme – what are the region’s differences and similarities in iron mining and processing. Geographically, we are very close, but, on the other hand, there is a different political structure and differences in economic activities and structures. There will be no 1:1 scheme, but we hope to find some common features; 6) to perform experimental archaeology and attempt the reconstruction of the iron smelting furnace,” A. Sne says.

The project implementation period is two years and its total costs are 480 850 euro, 10% of which will be provided by the Latvian state, 7,5% by involved institutions, but most – by the Norwegian financial instrument programme. Nineteen specialists, mostly from Latvia, will participate in the excavations and explorations.

CONFERENCE

CONFERENCE