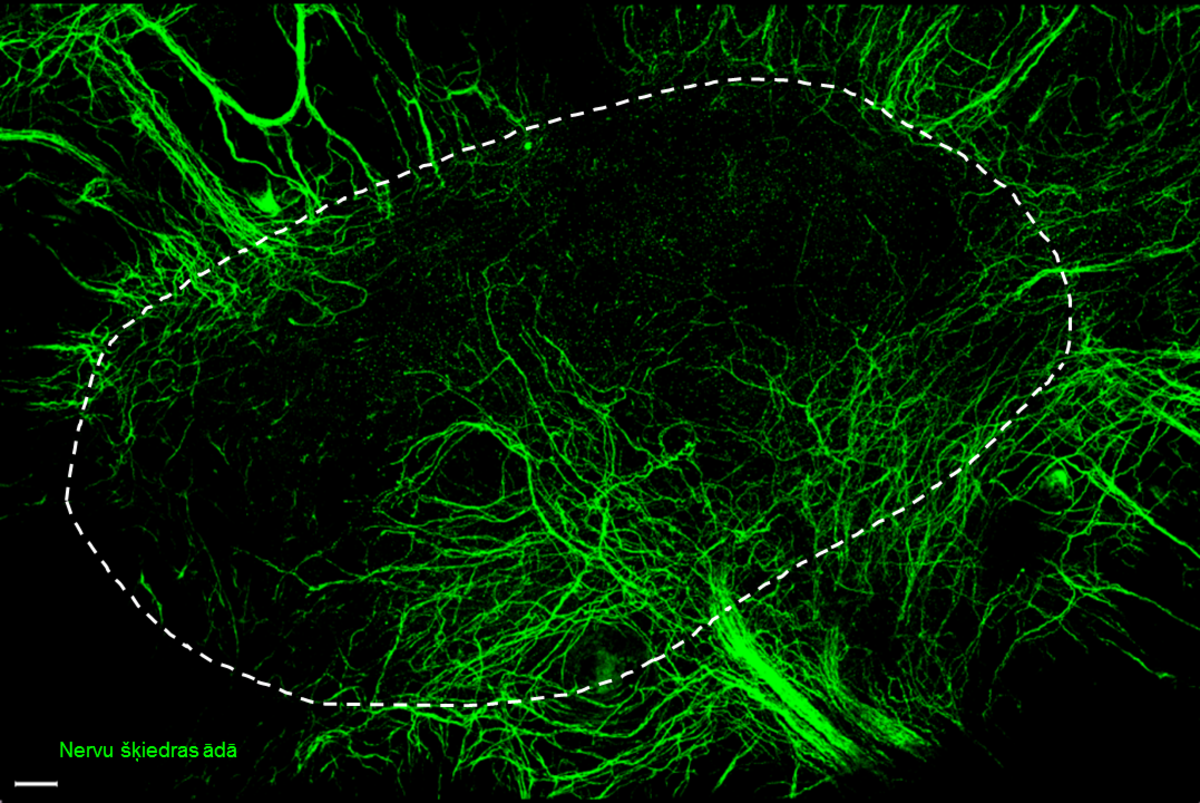

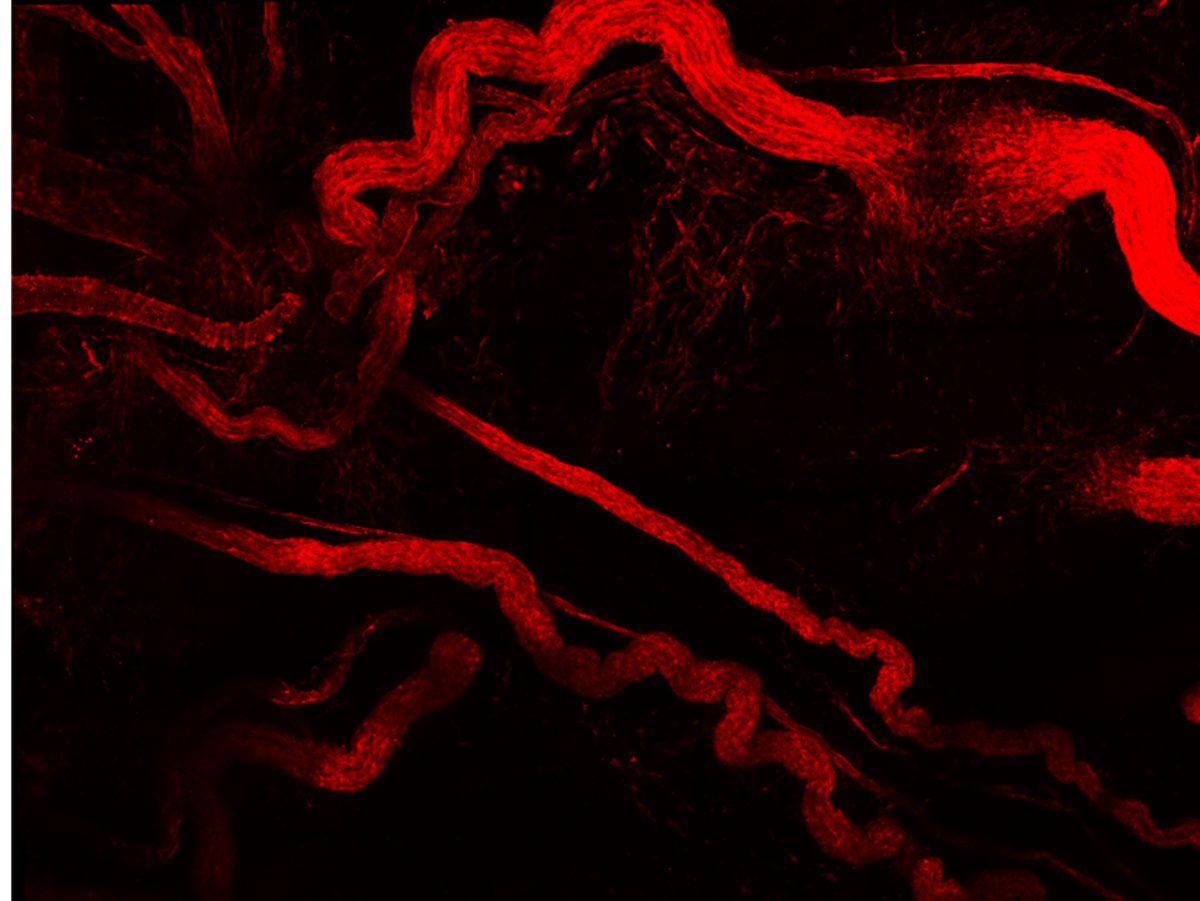

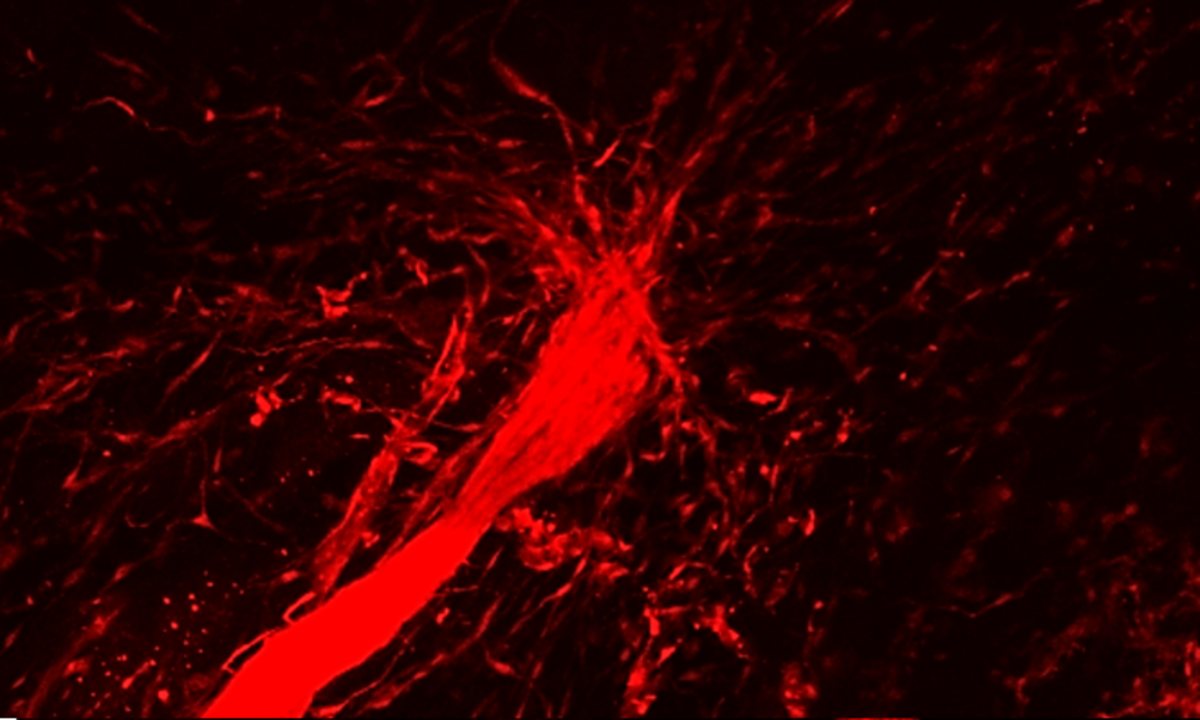

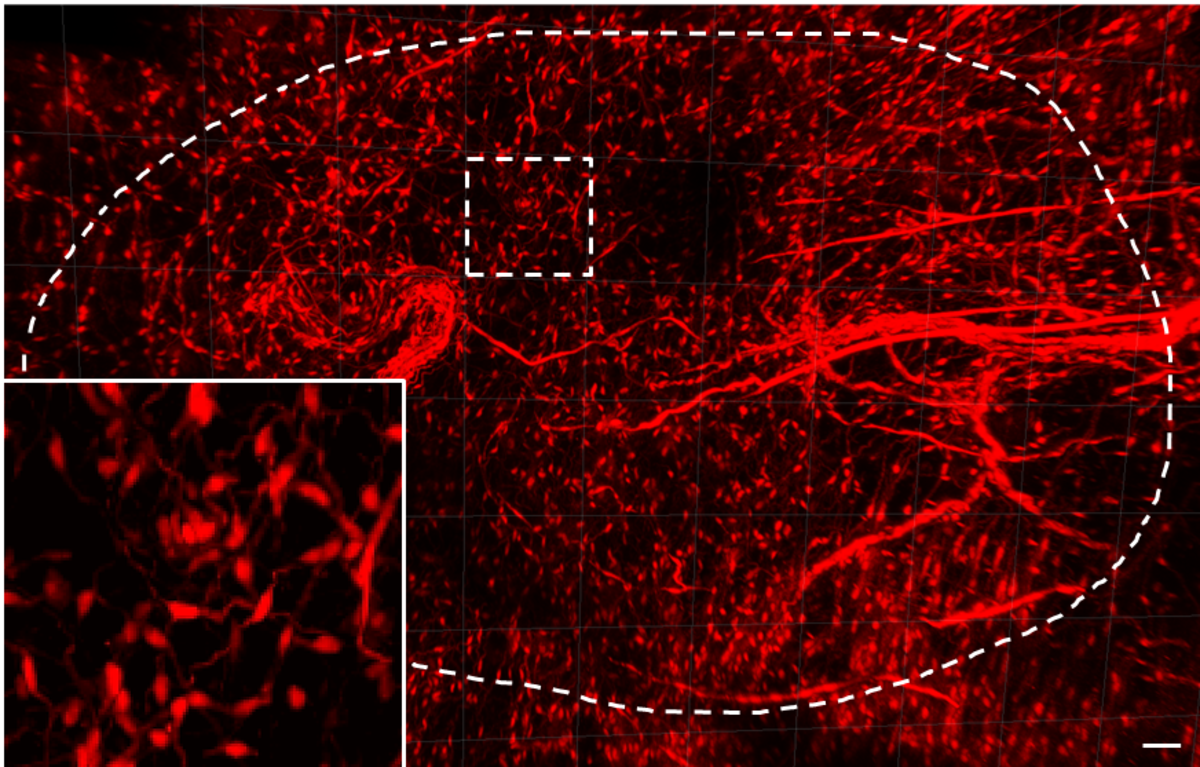

After a deeper injury to the skin, a scar remains. People can live with scars, but problems arise when scars occupy a significant part of the body, as is the case with burns, explains the author of the study, Dr. pharm. Vadims Parfejevs. Therefore, more profound understanding of the tissue healing and scar formation processes is important. The study has revealed one of the mechanisms that help wounds to shrink. After injury myelin sheath cells, or Schwann cells placed around the nerve fibres migrate to the wound area and promote wound closure.

In this process, the Schwann cells are undergoing significant changes and acquire the traits of stem cells. Judging by changes in the expression programs of activated Schwann cell genes, they release in wound proteins that stimulate healing by promoting the participation of other skin cells (such as fibroblasts) in healing process.

The study found that the healing process can also be hindered by genetic methods, preventing Schwann cells from migrating to the wound. Quick wound healing is not always beneficial, because it is usually associated with scarring. “Recently, a study has shown that older people have slower skin healing, but scar tissue that is formed is much thinner and smaller, it is rather a process of skin repairing itself that takes place. Slowing the healing process is likely to lead to better results,” emphasizes V. Parfejevs.

However, faster wound healing is needed in case of patients suffering from diabetes and diabetic foot syndrome causing development of ulcers that do not heal. "It has been previously observed that these people have a peripheral nervous system damage, they often do not feel touch, and the density of nerve endings is much lower than that of a regular person’s skin, which could indicate a possible connection with our research," the researcher explains.

In the course of the study, new biology methods were used to distinguish cells from normal skin and from a wound to analyse all the genes that are actively used in these cells after skin injury. Each gene encodes a protein, so the study produced a list of proteins that could be used to develop new medication. This protein list should name the candidate proteins to be incorporated into the wound dressing, enabling the proteins to enter the wound and carry out the same function – helping the wound to shrink quickly. This could help people with diabetes or patients with non-healing wounds.

It is possible that these same cells also have some role in the development of cancer, emphasizes V. Parfejevs, pointing out that there is a hypothesis that cancer is a non-healing wound. This is another potential research direction.

Another possible application is to incorporate these cells into artificial skin products that are used to replace the skin. For this purpose, a collagen gel is usually formed, wherein grow the cells of the most superficial layer of the skin – keratinocytes, and the deeper dermal layer cells – fibroblasts. This artificial structure could be supplemented with the Schwann cells, which would probably facilitate a faster reinnervation of the artificial skin.

The study "Role of peripheral innervation in wound healing" is one of the 12 most important scientific achievements in 2018.

The study "Characterization of neuroregenerative potential of human skin-derived cells in vitro and in vivo" was headed by Assoc. Prof. Una Riekstiņa at the UL FM doctoral study programme “Medicine and Pharmacy”, and enabled by the ESF project “Support for Doctoral Studies at University of Latvia”. The study on wound healing model in experimental animals was conducted between 2013 and 2017 by Prof. Lukas Sommer at the Institute of Anatomy, University of Zurich with the support of the Swiss Sciex-NMSch (Scientific Exchange) programme.

Academic Centre

Academic Centre